Contrary to popular belief attic ventilation is not a panacea for condensation or other moisture related problems that occur in cold climate attics.

In the colder months of the year while venturing into attics, it is not uncommon for me to find condensed moisture or frost present on the roof sheathing and nails. In fact, the colder the outside temperature, the more likely it is that I will see these conditions. In extreme, chronic cases, the roof sheathing has become stained black and may also have mold or other fungal type growth. In many instances the roofing nails have black spheres fading into the wood moving away from the nail. Conventional wisdom, which remains strong, I might say entrenched, is that increasing the attics ventilation will resolve the problem of excessive attic moisture. While this may sound reasonable at first, the science and more importantly reality do not support this assumption.

Attic ventilation “back in the day” was typically a set of gable end vents, which did a fair to poor job of venting the space. Other vent types were used, but by far the most common type I see on older homes are gable end vents. Later a whole attic approach was designed where a set of vents are used. A vent opening on the ridge of the roof with lower vents along the soffits. This upper and lower ventilation is more effective and efficient. The purpose of the vents, no matter the type, is two fold; to reduce heat in the summer months and dry incidental moisture in the winter months.

To dig into the science of why increasing attic ventilation will not solve and may even exacerbate attic moisture, it is first important to understand relative humidity. In the interest of full disclosure, I am not a scientist and psychometrics is a deep and complicated subject, however understanding some of its basic principles should be part of Home Inspection 101.

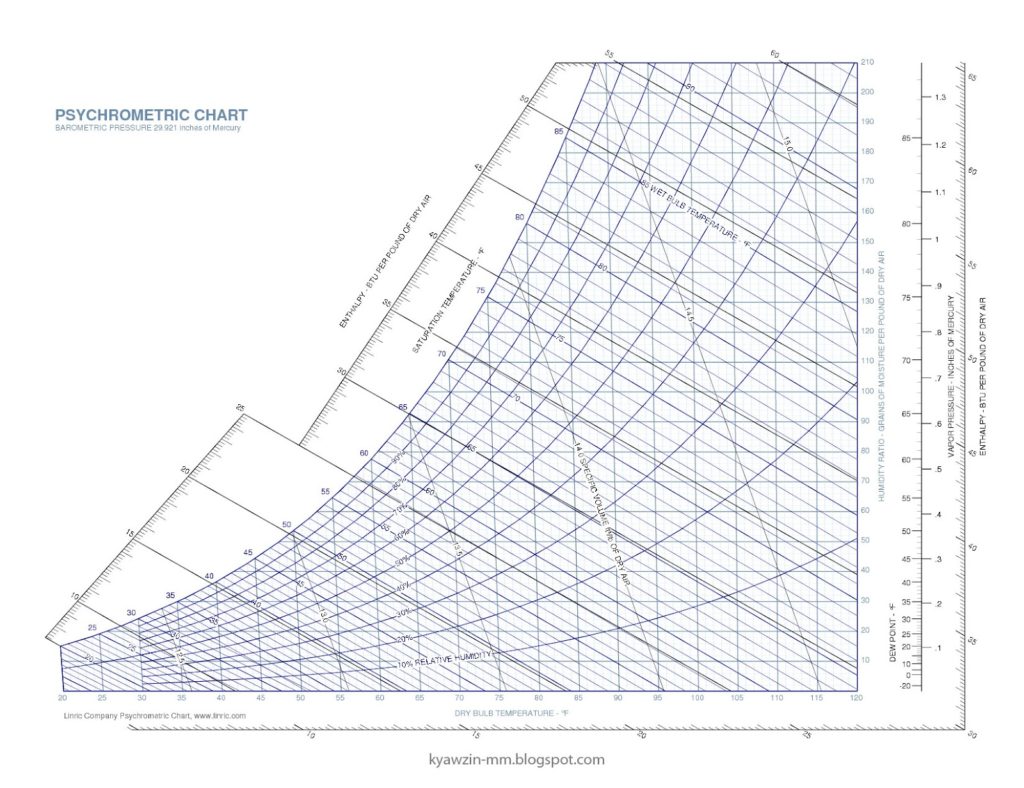

Relative humidity (RH) simply means the amount of water measured in a specific volume of air at a specific temperature. The psychrometric chart shown here is used to determine relationships with gases and vapors. When the RH inside a house is 40% at 70º F we can look at the chart and determine the dew point (DP) or at what temperature the water will condense out of the air. Additionally the chart can be used to determine the RH of that same air sample at varying temperatures. In this example the DP is about 44º F. If we reduce the RH to 30% the DP then becomes about 37º F. What should be apparent is RH increases as temperature decreases. That is why cold winter air is dry, because it has nearly no ability to hold moisture. This explains why when our nice comfortable, warm, reasonably moist indoor air finds its way into the wintry cold of the attic space, condensation can at times occur.

So if we know that winter air is dry, with no ability to absorb moisture, it then stands to reason, and the science fully supports this, that introducing more of this wintry air through more ventilation as a means of drying is in all likelihood not going to garner the desired result. Now it is true the air from the conditioned space will mix with the attic air lowering RH. However if condensation is occurring, adding ventilation brings other science based factors into the equation that as I said earlier can exacerbate the condition. By increasing ventilation, the air pressure in the attic space can become lower, pulling a greater volume of conditioned air into the attic. Air moves from higher pressure to low. Secondly warm air moves to colder air. These physical principles drive air and moisture into the attic that no amount of ventilation will likely reduce.

In reality adding ventilation to an attic space that is experiencing excessive moisture is like putting a band aid on your left arm, but the flowing gash is on your right leg. It not only entirely misses the problem, it does nothing to help it. The ceiling plane separates the living space from the attic and it is full of holes or bypasses. Add to that poor insulating, lack of or poorly installed vapor barriers and the means of transport is clear. Adding insult to injury, occupants sometimes mechanically add moisture to the living space through humidifiers. Other times the house sits on a wet basement or crawl space. All of these are factors to be examined when looking to correct excessive moisture when found in an attic.

I have and interesting and fun video to share that actually has numerous parallels to attic condensation and ventilation. The video discusses the fastest way to defog your windshield. The windshield could very well be the wet roof deck. Take note of the means necessary to remove the moisture from the windshield as well as the references to humidity and air. It’s all – ahem – relative.